This history was written in conjunction with AAFE’s 40th anniversary celebration.

For Asian Americans for Equality, it all began in the streets of Chinatown in 1974. Moved to action by a developer who refused to hire Asian workers for the massive Confucius Plaza construction project, local activists raised their voices, staged months of protests and finally prevailed. In so doing, they created a powerful grassroots movement that has endured for four decades.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, tumultuous national and world events were having a profound effect on Manhattan’s Chinatown. After strict immigration quotas were lifted in 1965, a large number of Chinese immigrants poured into the historic neighborhood, remaking the traditional ethnic enclave. Already difficult living and working conditions — including overcrowding and exploitation by employers — became worse in a community that had always been neglected by City Hall. At the same time, the Asian civil rights movement was gaining momentum, partially inspired by the black civil rights campaigns of the ’60s. Many young, idealistic New Yorkers of Chinese descent, some of them radical leftists, began focusing on Chinatown’s many troubling issues and decided the time had come to demand equal rights and equal access to city services.

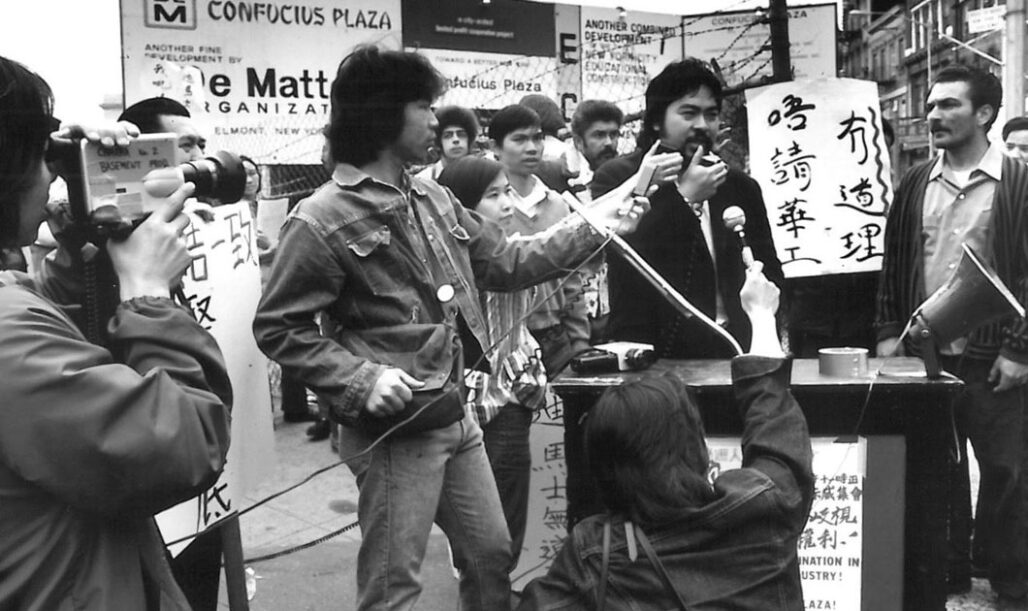

Throughout Chinatown, the injustices at Confucius Plaza were causing great outrage. The DeMatteis Corp., in charge of building the government-funded project, rejected pleas from the youthful activists, then known as Asian Americans for Equal Employment, to honor the city’s fair- hiring policies. Protests began May 16 and continued to pick up momentum through the fall. Picketers carried signs with slogans such as, “The Asians built the railroad; Why not Confucius Plaza?” Dozens were arrested.

A June 1 New York Times report noted, “The meticulously organized protest, similar to those that have been taking place at sites in black and Latino areas for 11 years in the city, is something new to Chinatown. While residents have often complained of discrimination and short-changing on city services, public protest has been rare.”

Reflecting on the dramatic events of 40 years ago, AAFE Executive Director Chris Kui says protest among New York Asians wasn’t just rare, it was unheard of at that time. “I remember the Asian community was afraid to speak up about issues they faced… lack of access to equal employment or services.”

DeMatteis Corp. eventually relented, agreeing to hire 27 minority workers, Asians among them. It was a major victory for the community and immediately established Asian Americans for Equal Employment as an organization that people could rely on when they had nowhere else to turn. The volunteers established an office in Chinatown, which quickly became a resource center for tenants facing harassment, those encountering immigration issues and workers being mistreated. There were more protests, too, against illegal sweatshops and deplorable conditions in local garment factories.

On April 26, 1975, another major controversy erupted in Chinatown, enraging the community and once again bringing the issue of civil rights for Asians to the forefront. After a minor traffic accident involving two motorists, one white and one Chinese, a large crowd gathered in front of the Fifth Precinct.

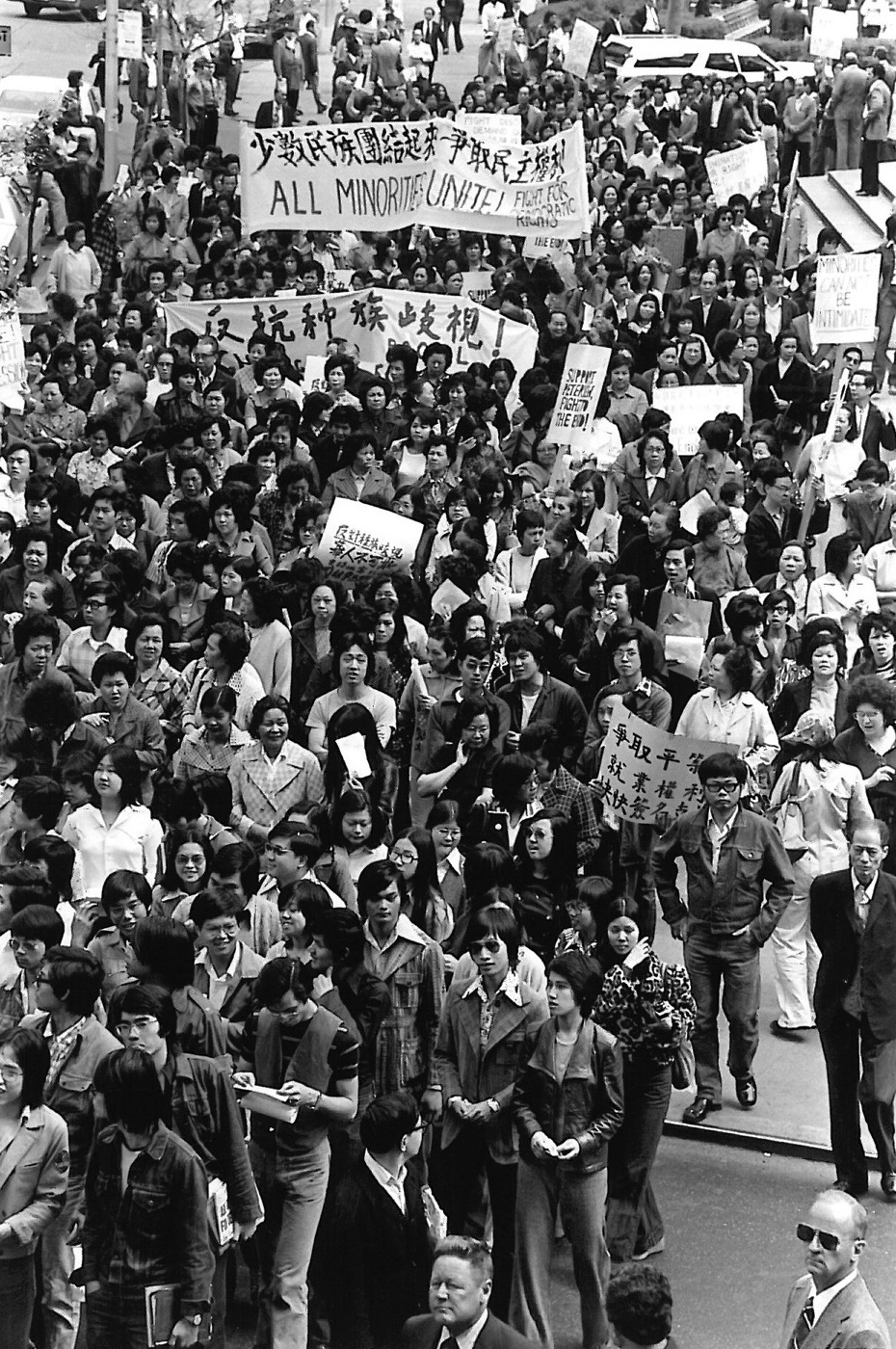

As police dispersed the crowd, they confronted a young architectural engineer, Peter Yew, and dragged him inside the precinct, where he was stripped and badly beaten. The incident touched a nerve, bringing long-simmering tensions between the Chinese community and police officers to the surface. Asian Americans for Equal Employment, along with many other local organizations, played a key role in mobilizing the neighborhood.

A rally against police brutality at City Hall brought out 20,000 protesters and forced the closure of most Chinatown businesses. After weeks of public pressure, all charges were dropped against Peter Yew on July 2 and an important message had been delivered to city leaders: the Asian community would no longer be silent.

Bill Chong, a former AAFE board president, notes that the protests in the ’70s “created a whole new image of Asians.”

“When people saw Asian protesters sitting in front of bulldozers at Confucius Plaza, or bringing 20,000 people to City Hall to protest police brutality,” he says, it changed the perception that “we were too timid to protest.”

Chris Kui also remembers it as a turning point: “There was a lot of discussion within the community. Some people said ‘Let’s not make trouble… it could hurt our future.’ Others even said ‘This isn’t really our country.’ But a whole new generation had a different view and said ‘This is our country. We have rights. Let’s fight for those rights.’”

In 1977, three years after the organization was founded, its name was changed to Asian Americans for Equality to reflect an expanding mission. Leaders reached out to other ethnic groups and joined coalitions involved in important issues both close to home and abroad. AAFE was part of a broad campaign to fight city budget cuts, it helped win the first union contract for workers at a Chinatown restaurant and secured compensation for customers of a local bank after their safe deposit boxes were burglarized. The organization also joined nationwide civil rights actions. Chief among them was the protest movement that sprung from the brutal murder of Vincent Chin, a 27-year-old engineering student in Michigan who was beaten and killed in June of 1982 by two men who blamed Asians for the loss of auto jobs to Japan. The tragedy was a wakeup call for Asian Americans that galvanized communities and inspired groups such as AAFE to take the fight for justice and equality to a new level.

Meanwhile, the situation in New York City remained troublesome. Residents were flocking to AAFE’s community clinics with alarming stories about the state of the neighborhood’s housing stock. Large numbers of people were living in substandard spaces that had been illegally divided. Landlords brazenly ignored building codes and shut off hot water and heat. As surrounding downtown neighborhoods became more desirable, real estate prices soared and property owners sought to evict low income tenants. In response, AAFE launched a campaign called “Fight Gentrification & Save Chinatown,” which created tenant associations in many buildings and trained tenant leaders.

But as it turned out, an even bigger threat to affordable housing was looming on the horizon. The administration of Mayor Ed Koch quietly pushed through a “Special Manhattan Bridge District,” which encouraged the construction of high-rise luxury condominiums in place of low-income tenements. AAFE and other community organizations quickly mobilized to oppose the scheme. in 1983, AAFE filed a class-action lawsuit against the city and won an initial legal victory. While the ruling was partially overturned, the court case had the desired effect, largely discouraging developers from exploiting the neighborhood.

The innovative legal strategy saved Chinatown from real estate speculators, but it also had a wider impact. Chris Kui explains: “No one in an urban setting at that time was talking about inclusionary zoning,” a mechanism for creating some affordable units in privately built projects and is today a pillar of New York’s housing strategy. “We used it to fight the Special Manhattan District,” he says. It got statewide attention. Courts ruled that the city had an obligation to zone for the benefit of everyone, not just property owners.”

In these years, there was a growing realization that the immense challenges facing Chinatown could not be effectively addressed by an all-volunteer organization. In 1983, Doris Koo became AAFE’s first executive director and a plan was put in motion to become a non-profit organization and hire a full-time professional staff.

In the aftermath of AAFE vs. Koch, it became clear that the fight for affordable housing would define Asian Americans for Equality in the years ahead. A tragic 1985 fire on Eldridge Street accelerated the organization’s push into housing development. But throughout the years, AAFE never lost sight of its roots in social justice and community advocacy.

Looking back on this period, Doris Koo observes that AAFE was changing along with the country, adapting to the post-protest era in America. It was “a time to codify the values” that had been established in the early years and to “put those precious, fragile beliefs” into “a foundation for practical work.” This meant, among other things, not just effecting change from the outside but actually having a “seat at the table” and helping to shape the city’s future.

Despite the large spike in Chinatown’s Chinese population, relatively few citizens participated in the political process. There was, for example, not a single Asian representative on the New York City Council. So AAFE placed a great emphasis on increasing civic activism among Asian Americans — registering voters, educating community members about important issues and engaging with elected officials, community boards and other organizations.

As the decade wound down and the 1990 U.S. Census approached, AAFE recognized it as a big opportunity to change the political dynamic. The organization formulated a redistricting proposal, one that would give an Asian American candidate a fighting chance of winning a seat on the council, representing Chinatown and other Lower Manhattan neighborhoods.

In 1991, Koo told the New York Times, “We are the last group to get energized and politicized. The time has come.”

After a contentious debate, the proposal was approved by the Redistricting Commission, and Margaret Chin, an AAFE founder and former board president, entered the Democratic primary in the newly formed Council District 1. While she did not prevail in that election, Chin persevered through the years and was finally victorious in 2010, becoming the first Chinese American to represent Manhattan’s Chinatown and the first Asian woman to serve on the City Council.

“We overcame so many obstacles, but the final result is victory,” Chin said during her victory celebration in Chinatown, attended by a broad cross section of well wishers. “For it to finally happen, it is very significant,” Chin asserted, adding that the older Chinese population, in particular, was finally being heard after being marginalized due to language and cultural barriers.

There were other breakthroughs for Asians in that election. John Liu, having already served on the City Council since 2001, was poised to become the first Asian to win citywide office in New York as city comptroller. In Flushing, Queens, Peter Koo was on his way to winning a council seat. More victories followed. In 2012, Grace Meng became the first Asian American congressional representative from New York, and Ron Kim was elected to the State Legislature, becoming the first Korean American in that body.

Chris Kui calls AAFE’s campaign to increase Asian representation a keystone accomplishment, The founders, he says, “knew that unless we had our own representatives we would never be able to pursue the dream of equality and justice for the community.” But, he adds, there’s still much work to be done. Asians now make up 13 percent of the city’s population, yet elected representation at all levels of government continues to lag. “So (today) that’s why we expend a lot of resources educating and registering voters. That work is continuing.”

In partnership with elected officials, government agencies and other non-profit organizations, AAFE has advocated on a wide range of issues, including immigrant rights, equity in public funding and quality recreational spaces in local communities. One high priority has been the problem of “demolition by neglect,” in which unscrupulous owners of rent-regulated buildings seek to drive low-income tenants from their homes. AAFE authored a 2011 research report on the subject, highlighting some of the worst offenders and laying out policy solutions.

In 2009, AAFE was on the scene of a fire in Manhattan’s Chinatown, at 22 James St., which left three people dead and many others injured. After dealing with the immediate crisis, AAFE worked to prevent the demolition of the tenement by organizing the tenants and keeping pressure on the owner to make repairs. A year later, Asian Americans for Equality were there to welcome the residents home.

In 2010, an even larger fire swept through almost a full block of Grand Street, displacing hundreds of residents. AAFE took the landlord of one of those buildings to court, after the owner insisted demolition was the only option. A judge ruled in favor of the tenants, and three years later they, too, moved back to their affordable apartments. Speaker Silver, who partnered with AAFE and city housing officials on the effort, called it “a great victory for those of us who have fought for the preservation of affordable housing in Chinatown and throughout our city.”

Through the decades, AAFE has stayed focused on ensuring equality for all. Even today, as the organization works hand-in-hand with government agencies and manages a large housing portfolio, it remains mindful of its roots. That’s not to say AAFE’s strategies have stayed the same. They have, indeed, changed to reflect the times.

As the 1990s drew to a close, the organization increased its outreach to a wide array of Asian groups, forming coalitions to meet the needs of rapidly growing constituencies. In the year 2000, AAFE created Chhaya Community Development Corporation to advocate for the housing needs of New York’s South Asian community. A year earlier, AAFE formed the National Coalition for Asian Pacific American Community Development. It was the first group dedicated to addressing the housing, community and economic development needs of the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities.

Through these alliances, AAFE built on the founders’ determination to create a truly pan-Asian organization, while amplifying the dreams and aspirations of an increasingly diverse community.

Chris Kui concludes, “Today I think we are able to work with a broader strata of people throughout the city, building coalitions, talking to legislators and then going out and making policy changes. So it’s not just organizing direct action, but it’s really using protest as part of the strategy tool kit, but at the same time putting forth potential positive solutions.”

A Community Advocate Becomes a Community Builder

On the bitterly cold evening of January 21, 1985, the residents of 54 Eldridge St. were forced to rely on portable electric heaters because the building had no centralized heat or hot water. That night, the strain on the old wiring in the dilapidated tenement was too much, and a fire started. It spread quickly, destroying the building. Tragically, two elderly tenants were killed and 125 left homeless.

During its first 10 years serving Chinatown, Asian Americans for Equality had been witness terrible housing conditions throughout the neighborhood. Its focus on tenant organizing, fighting illegal landlord practices and educating people about their rights had made a significant difference. But the awful events on Eldridge Street that night showed very clearly that those early efforts would be insufficient. In order to make greater strides, AAFE would need to find a way to create new housing options.

In that moment, there was no grand plan to become an affordable housing developer. The Red Cross had called AAFE in to help deal with the emergency situation. Executive Director Chris Kui recalls, ”We worked with the city to place people in shelters, but a lot of folks wouldn’t go because the shelters were in terrible condition, or they couldn’t communicate and didn’t want to leave Chinatown.” So the organization, very often at its most innovative during a crisis, came up with a solution for the future: build a new downtown shelter.

But reaching that goal during the presidency of Ronald Reagan would be a challenge. Homelessness was a big issue. There was virtually no public funding available for a temporary facility, and public housing was subject to draconian budget cuts. One new program that had just been introduced, however, provided a unique opportunity.

AAFE acquired two buildings seized by the city — 176 and 180 Eldridge St. — and was able to attract financing by utilizing the Federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit. The development, named Equality House, consisted of 59 apartments for low-income and formerly homeless residents. The Enterprise Foundation, an affordable housing pioneer, and Fannie Mae partnered with AAFE for the $5.2 million rehabilitation project. There were setbacks, including another fire that gutted the buildings, but the organization persevered. Equality House became a national model. Bill Frey, an Enterprise Foundation executive, called it a breakthrough project. ”(Equality House) became the model that really has provided the initial way for us to do this around (New York City).”

It was the first, but certainly not the last, time Asian Americans for Equality created a widely emulated affordable housing strategy. Years later, Jerilyn Perine, a former commissioner of New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, said, ”They’ve been willing to take risks with us on new program models, and it has sometimes made their work much tougher because they went first… (But) the fact that they’ve been willing to do that has been really helpful.”

In the years following the Equality House triumph, AAFE acquired and renovated more buildings in Chinatown and on the Lower East Side, providing desperately needed housing for low-income tenants and seniors. Projects such as Clinton/Peace Houses, which created 22 apartments in two formerly city-owned buildings upon opening in 1992, attracted thousands of rental applications. AAFE emphasized reaching out to a broad range of ethnic and racial groups with the aim of operating buildings that reflected the diversity of the local community. As each building conversion was completed, government agencies and funders became increasingly confident in AAFE’s abilities as an adept not-for-profit developer.

By 1997, 11 buildings had been rehabilitated and AAFE was managing 200 apartments. That year, a non-profit developer on the Lower East Side known as Pueblo Nuevo became mired in scandal and abruptly went out of business. AAFE was asked to take over work on nine buildings the group had been renovating and successfully got the project back on track. Its management of the difficult situation further embellished the organization’s reputation and led the Fannie Mae Foundation to present AAFE with the prestigious Maxwell Award of Excellence.

In 1998, the initial phase of the organization’s first-ever new construction project, Norfolk Apartments, opened to renters. The seven-story building created 24 low-income units and a ground-floor community space. It was supported by the New York State Housing Trust Fund, federal low-income housing tax credits and the Enterprise Social Investment Corporation.

“Norfolk Apartments II,” the second, more extensive phase, added 54 apartments for working families and seniors in new buildings on three additional parcels on Norfolk and Stanton streets. The September 11th terrorist attacks threatened the project, but AAFE was determined to show its resolve and proceed, in spite of the obstacles. Construction began in January 2002. When the lottery opened for apartments, the response was overwhelming. Frank Lang, former director of planning and development, said, “I feel very proud that we broke ground just a few months after the disaster… It sent an important message that we would be there, no matter what, to help the future of this neighborhood.”

From the ashes of 9/11, opportunities to help the hard-hit neighborhoods of Lower Manhattan emerged. The Lower Manhattan Development Corp. established a $16 million fund to acquire and preserve affordable apartments in Chinatown and the Lower East Side. Through this program, AAFE was able to purchase privately owned buildings, renovate more than 130 apartments and assure their place in New York’s rent stabilization program for years to come.

In 2013, AAFE became the first non-profit organization to partner with the city in a new program that seeks to redevelop distressed properties as low-income cooperatives. The $3.9 million project, located at 244 Elizabeth Elizabeth St., would become a model for future building conversions, utilizing the newly Affordable Neighborhood Cooperative Program (ANCP). AAFE Board President Wendy Takahisa says it’s a perfect example of the organization’s willingness to tackle new challenges. “It’s a tough program,” she explains. “There haven’t been a lot of groups willing to take it on. It requires tenant organizing. A tenant cooperative is a very difficult structure. You need to line up financing. But I think there’s a good chance it will be a successful building because AAFE has the necessary skills to make it work.”

Homeownership has, of course, long been integral to the American dream. It’s particularly important to immigrants as they begin to establish roots and develop a sense of belonging in their new country. In the late 1990s, AAFE seized a unique opportunity, building 48 townhouse-style condominium units on Suffolk Street on the Lower East Side. This project was designed to fill a growing need for middle income housing in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. But it was only a small part of AAFE’s overall homeownership strategy, which has provided critical support to thousands of low and middle income families across the five boroughs of New York City. AAFE Executive Director Chris Kui explains, “We saw that there was a need to help people secure financing for their own homes, so we got involved in direct lending and in mortgage counseling.”

Following Hurricane Sandy in 2012, AAFE responded with emergency support for homeowners in many hard hit neighborhoods in Manhattan, as well as devastated Brooklyn communities in Coney Island, the Rockaways and other locations. Even under normal circumstances, the types of clients AAFE serves have trouble borrowing money for home improvement projects. They often need small loans, often less than $30,000, which have become difficult to secure from conventional lenders in the aftermath of the 2008 financial collapse.

After Superstorm Sandy, AAFE came to the aid of many homeowners, providing more than $1 million during a 12-month period for emergency repairs. AAFE Community Development Fund has continued to provide Sandy-related loans – not only in traditional Asian neighborhoods such as Sunset Park, Brooklyn but also on Staten Island and other hard-hit areas in which AAFE previously had little presence. Today, approximately 40 percent of those receiving assistance are Latino or African American. The organization has provided a range of services, helping homeowners hire contractors, develop work plans, install energy efficient appliances and avoid foreclosure proceedings.

“The Asian community has grown beyond the traditional Chinatown communities,” Chris Kui says, “and AAFE saw itself as a very neighborhood-based organization. It’s a place-based approach, but at the same time it is people-based. As the population has grown, Asian immigrants settled in many different areas, and we grew with them.”

Asked what is behind the organization’s success as a non-profit housing developer, Kui points to the affordable housing void in the 1980s and 1990s, when the private developers in today’s industry did not exist. “We saw a need to preserve and to build apartments or to help people get the financing to buy their own homes. We got involved in mortgage counseling, to help people see they could live in neighborhoods beyond the traditional Asian enclaves. It’s happened because we were flexible and nimble.”

Creating Economic Opportunity

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, sent the Lower Manhattan community reeling. Asian Americans for Equality, headquartered just a few blocks from ground zero, was in a unique position to help New York cope with the unprecedented crisis and to lead the devastated Chinatown community in its aftermath.

After 27 years serving the neighborhood, it was only natural that emergency agencies turned to AAFE for its expertise and deep understanding of the local community. The evening of 9/11, staff members worked inside disaster centers and, in the days following the attacks, helped frightened immigrant residents apply for government aid. As the immediate crisis passed, AAFE was the driving force behind a multifaceted campaign to inject Chinatown’s businesses with desperately needed capital and to create a comprehensive plan for the neighborhood’s future.

This monumental effort was spearheaded by Renaissance Economic Development Corp., an entity created by AAFE in 1989 to support fledgling small businesses and to provide economic opportunity for new immigrants throughout New York. Four years before the September 11th attacks, Renaissance had become a community development financial institution, certified by the U.S. Department of the Treasury. While it had been empowering entrepreneurs for several years and making a significant impact, the 9/11 tragedy was a defining moment for Renaissance and AAFE as a whole.

“It was definitely a very proud moment for AAFE,” says Executive Director Chris Kui. Federal emergency management staff, he explains, “didn’t have the language skills, they didn’t understand the community when they were shaping programs. I think AAFE was able to rise to the occasion mostly because we had been in the community for many years and we had already been providing assistance to small businesses in the area. City, state and federal agencies sought us out.”

Historically, AAFE’s first impulse has always been to act swiftly when there are pressing community needs. It was no different following 9/11. Rather than waiting for help to arrive, Renaissance took the step on September 21 of creating a $150,000 emergency loan fund for struggling small businesses by diverting money from its operating budget.

While the initial amount was relatively small, it was an important step in demonstrating to government officials that the community had an acute need for direct financial assistance. Early on, they were preoccupied with the immediate area around ground zero and largely overlooked Chinatown. The neighborhood was barricaded, utilities were cut off, and businesses, many of them largely dependent on tourism, were suffering. Eventually, 7,700 jobs would be lost, and Chinatown’s already hobbled garment industry would be decimated.

In the months that followed, AAFE secured more money and closed 150 loans. Later the organization worked with the Empire State Development Corp. to distribute $15 million in loans. Corporate and foundation money eventually started to trickle in, bolstering efforts to stabilize the local economy. City and state leaders ultimately showed their confidence in AAFE as a community partner by asking it to be a main administrator of the $300 million Residential Grant Program from the Lower Manhattan Development Corp.

In 2002, AAFE launched the Rebuild Chinatown Initiative, a community-driven project to create a blueprint for the revival of the neighborhood. It attracted initial financial support from the Fannie Mae Corp. The two-year process, which included extensive outreach across Chinatown, laid out short- and long-term programs to jump-start economic life and to address long-standing problems, such as sanitation, transportation and, of course, affordable housing. Through Rebuild Chinatown’s recommendations, approximately $100 million was invested by public and private funders to strengthen Chinatown. In 2004, the project received the Meritorious Achievement Award from the New York Metro chapter of the American Planning Association.

While AAFE’s economic development activities accelerated greatly in the years after 2001, fostering entrepreneurship had been a longtime priority.

In the insular world of Chinatown, language difficulties, cultural barriers and a lack of familiarity with the American financial system prevented many immigrant business owners from acquiring capital. The organization, seeking money for affordable housing projects, experienced rejection from banks located in the neighborhood. AAFE’s first housing project was turned down by 15 banks. So the organization conducted a survey and found that, between 1988 and 1990, 33 Chinatown banks were sitting on $3 billion in deposits.

Doris Koo, executive director in these years, argued that community residents who placed their hard-earned wages in those banks had a right to access their capital. “They are the first generation of immigrants who said we will sacrifice so our children will have a better future,” Koo maintained. “All that hard work, all that sweat that went into the sweatshops and restaurants goes right into a bank account.” To make its case, AAFE utilized the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act, which was meant to encourage banks to offer credit in communities they served. Eventually several banks agreed to offer credit to Chinatown small-business customers.

Since its founding, Renaissance has provided more than $30 million in affordable loans to almost one-thousand small businesses and entrepreneurs. Targeted at diverse communities, the organization offers much-needed financing for small firms to grow their existing services or products, or to launch new ventures. The focus is on relieving the credit crunch for women, immigrant and minority entrepreneurs. Services provided help overcome language and cultural barriers, opening doors for innovation. In 2012 alone, Renaissance facilitated nearly $5 million in loans, creating 137 jobs.

Loans of up to $100,000 can be used for the purchase of supplies, inventory, equipment or for renovations of commercial real estate. There are programs focused on emerging and developing communities such as Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, Bay Ridge and Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, as well as Flushing in Queens and communities throughout New York City. AAFE is one of the nation’s top producers of micro-loans from the Small Business Administration. Renaissance also provides training and expert advice to business owners on topics such as obtaining patents, franchising, improving sales, launching marketing campaigns and management. There’s a 12-week intensive training program for first-time owners, which draws on the expertise of representatives from the IRS, financial institutions and law firms.

In 2008, AAFE became a member of NeighborWorks America, one of the country’s most respected community development and affordable housing organizations. Chartered by the United States Congress, NeighborWorks’ board includes some if the federal government’s key finance and housing decision makers. As part of the nationwide network, AAFE’s programs have received important funding but, even more significant, NeighborWorks has provided invaluable training and technical assistance, helping AAFE better serve its communities.

Poised to enter its 39th year, AAFE reprised a familiar role — that of first responder in an emergency situation. In October 2012, staff members scrambled to help deal with the devastating effects of Hurricane Sandy. Hours after the storm came ashore, they were knocking on doors throughout Lower Manhattan, delivering food and medicine to the homebound and assisting in cleanup efforts on the Lower East Side, as well as in the hard-hit communities of Brooklyn and the Rockaways. Once again, AAFE was there, on the ground, long before government agencies could mobilize

Board President Wendy Takahisa says, “AAFE was really able to play a major role in helping people throughout the city both in neighborhoods in which people woke up and realized they had an Asian American population that they maybe never noticed, that had been flying under the radar, but even in the broader community, helping in the Rockaways and Coney Island, where there was a lot of need, and AAFE brings a lot of expertise.”

Renaissance came to the rescue, too, activating two emergency loan programs for impacted businesses as well as homeowners. The first loan checks were cut just two days after the disaster. AAFE distributed $6 million in emergency loans to hundreds of small businesses in in the first few weeks. No other entity was able to get funds directly out to local small business owners so swiftly.

AAFE’s Chris Kui recalls, “small businesses, in particular, were especially impacted by the loss of sales. Restaurants, for example, lost their entire inventories. Wholesale businesses and warehouses on the waterfront flooded. A low-interest loan of $30,000 made a big difference for these small businesses that needed immediate assistance.” The organization’s economic development programs have served as an essential safety net in times of crisis. Kui says, “AAFE has become very much a model of a social firehouse. We are in the community. We can respond in times of emergency.”

Enriching Our Communities

Asian Americans for Equality has a reputation for pioneering big ideas and overseeing complex development projects. But oftentimes, at the community level, some of the simplest initiatives have the greatest impact.

Maybe it’s leading high school students on a college tour. It could be showing a child how to ride a bike as part of the “Local Spokes” coalition that AAFE helps lead. Perhaps it’s a computer literacy tutorial for a senior citizen. Almost since its earliest days, the organization has placed a high value on empowering its communities through education, training and engagement in New York City’s neighborhoods.

Wendy Takahisa, president of AAFE’s board of directors, is proud of the organization’s accomplishments as an affordable-housing builder and as a small-business lender. But, she says, the “brick-and-mortar community development has to go hand-in-hand with community building. It comes with being a community quarterback.” That means helping natural leaders within the community to find their own voices, to galvanize their friends and neighbors behind a cause and to become their own best advocates.

This role of “community quarterback” takes on many different forms. AAFE helps people secure their entitlement benefits. The organization became a federal health-care navigator, guiding residents through Obama Care. Staff members coordinate voter-registration drives and offer youth leadership and adult leadership programs; they organize trips to Albany to advocate for important issues with state legislators. Takahisa explains, “There is a big role for building leadership, and I think some of the most exciting things I have seen done at AAFE are in this area.”

Cultivating leadership is not a new phenomenon for AAFE. In the 1970s, tenant organizing workshops were held in Chinatown to educate people about their rights. It’s still an important advocacy tool today, often making it possible for residents to stay in their homes against all odds. Today, however, community building at AAFE is remarkably diverse, encompassing a wide range of advocacy, empowerment and education initiatives.

At Flushing High School, for example, AAFE has made a long-term commitment to helping students pursue their dreams of going to college. In many cases, these young people are the first members of their families to pursue higher education. AAFE’s programs are focused on college readiness, financial capability and parent engagement. Students from Flushing High School, as well as Flushing International High School and Lower East Side Prep in Manhattan have the opportunity to visit college campuses and to stay overnight. Workshops cover topics such as the college application process, writing personal statements, budgeting, stress management, and relationship building.

For parents, programs encourage involvement in teacher conferences and other school events, and language translation services are provided. Douglas Nam Le, director of policy and leadership development, says AAFE’s college readiness programs are not simply about placing the largest number of students in top flight universities. “Some might get a full ride to MIT,” he says, “but others succeed in their own ways by achieving individual academicgoals, often despite challenging circumstances. The programs are aimed at lifting them up.”

Another important initiative in local high schools is AAFE’s peer-to peer counseling program. In partnership with, “College Access: Research and Action,” young people are trained to help other students prepare their college applications and to apply for financial aid. Youth leaders have trained 700 students, serving as positive role models.

In Sara D. Roosevelt Park in Manhattan’s Chinatown, AAFE volunteers routinely take part in “It’s My Park Day,” helping to pick up trash, to pull weeds from gardens and to take part in community building activities. Through its involvement with the Sara D. Roosevelt Park c\Coalition and neighborhood groups in Queens and Brooklyn, AAFE advocates for more green space and equity in parks funding. Recycling programs, including an initiative encouraging restaurants to properly dispose of cooking oil, build greater environmental awareness. AAFE’s “Go Green Western Queens” project is focused on organizing young people and community residents to promote stewardship of green assets and to conserve energy.

In East Harlem, AAFE joined a coalition of elected officials and non-profit organizations to speak out against a series of attacks against Asian residents in 2013. The efforts were focused on ensuring that the police department’s outreach efforts extended to all segments of the community, including non-English speakers. The organization provides a range of personal safety education programs, including fire safety and disaster preparedness workshops.

It’s important to recognize that AAFE’s community-based programs do not take place in a vacuum. They are interwoven with the organization’s broad mission to help make the city better for all of its residents. This spirit is on display each year at AAFE’s Community Development Conference. The prestigious event, held at New York University Kimmel Center, brings together leaders in community development, government, advocacy, philanthropy and the private sector. The mission is to advance ideas for preserving and enhancing neighborhoods, creating greater economic opportunity and bolstering the Asian American community’s nationwide influence.

The conference, as well as many partnerships AAFE has formed across New York, has established the organization as a community development leader. AAFE Executive Director Chris Kui says, “In working with other minority groups, we see the empowerment of the entire city. We build coalitions with other ethnic and social groups. We want to make sure it’s not about one ethnic group, benefiting only the Asian community.”

When it comes to AAFE’s grassroots work, Wendy Takahisa is reminded of the 1911 poem originating from the union movement in Lawrence, Massachusetts, which made famous the following phrase: “We want bread, but we want roses, too!”

She concludes, “I think AAFE has always been about bread, bricks and mortar, you know, people need a place to live. But we are also about how you build a good quality of life.”